https://en.sputniknews.africa/20240907/unveiling-the-unknown-genetic-and-environmental-factors-behind-cleft-lip-and-palate-1068189427.html

Unveiling the Unknown: Genetic and Environmental Factors Behind Cleft Lip and Palate

Unveiling the Unknown: Genetic and Environmental Factors Behind Cleft Lip and Palate

Sputnik Africa

A cleft lip and palate are congenital conditions where a baby is born with openings or splits in the upper lip and the roof of the mouth (palate). A cleft lip... 07.09.2024, Sputnik Africa

2024-09-07T17:30+0200

2024-09-07T17:30+0200

2024-09-10T12:21+0200

opinion

southeast asia

indonesia

vietnam

south africa

southern africa

surgery

healthcare

app

technology

https://cdn1.img.sputniknews.africa/img/07e8/09/07/1068189736_0:67:1280:787_1920x0_80_0_0_23f9f0e215b20e40a7fecf4956bb164a.jpg

Only about 5% of cleft lip and palate cases can be traced back to genetics, leaving a staggering 95% in the realm of the unknown, Professor Anil Madaree, Head of the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, told Sputnik Africa.This uncertainty points to a complex interaction between genetic makeup and environmental factors that researchers have yet to fully unravel.Cleft lip surgeries are typically performed when the child is between 3 and 4 months old, while cleft palate surgeries usually occur between 9 and 12 months of age. Post-operative care is crucial, particularly for cleft palate cases, where diet and feeding must be carefully managed to prevent complications.Interestingly, in some parts of the world, such as Southeast Asia, cleft conditions are more prevalent.Addressing these challenges, organizations like Operation Smile, with which Professor Madaree is deeply involved, work tirelessly to provide care and build local capacity. He emphasized that it's not only about performing surgeries, "but more importantly is to try and educate the local people, all the healthcare workers […] [to make] a long-lasting impact."Looking to the future, Professor Madaree envisions the potential for emerging technologies to revolutionize cleft treatment.But even with existing technology, people with this condition get excellent results. Sputnik Africa talked to one of them to learn about his experience.Tshepo Manetja's life changed when he was born with a cleft lip and palate. Although he received surgery to repair his cleft lip as a baby, the surgery for his cleft palate was repeatedly delayed. For years, Tshepo lived with the condition, until one day in 2018, he saw an advert for Operation Smile on DStv and reached out.In February 2019, Tshepo's long-awaited surgery was performed by Professor Madaree during Operation Smile's surgical program at Witbank Hospital in Mpumalanga. The surgery was successful, and for the first time, Tshepo experienced life without the gap in his mouth.Now, with all his surgeries complete, Tshepo is on a new journey—getting his teeth straightened. Thanks to Operation Smile's continued support, he is receiving orthodontic treatment at Charlotte Maxeke Academic Hospital.As the medical community continues to explore the unknowns of cleft lip and palate, the hope is that with a blend of scientific discovery, technological advancement, and global collaboration, these conditions can be better understood and treated worldwide.

https://en.sputniknews.africa/20231225/senegalese-young-man-disfigured-by-disease-recovers-face-in-russia-1064301137.html

southeast asia

indonesia

vietnam

south africa

southern africa

Sputnik Africa

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2024

Christina Glazkova

https://cdn1.img.sputniknews.africa/img/07e7/0b/07/1063380906_0:0:673:674_100x100_80_0_0_79628b4d0cd9f29291a57aa13bbf9e7a.jpg

Christina Glazkova

https://cdn1.img.sputniknews.africa/img/07e7/0b/07/1063380906_0:0:673:674_100x100_80_0_0_79628b4d0cd9f29291a57aa13bbf9e7a.jpg

News

en_EN

Sputnik Africa

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik Africa

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Christina Glazkova

https://cdn1.img.sputniknews.africa/img/07e7/0b/07/1063380906_0:0:673:674_100x100_80_0_0_79628b4d0cd9f29291a57aa13bbf9e7a.jpg

southeast asia, indonesia, vietnam, south africa, southern africa, surgery, healthcare, app, technology, health ministry, health, disease, africa in details

southeast asia, indonesia, vietnam, south africa, southern africa, surgery, healthcare, app, technology, health ministry, health, disease, africa in details

Unveiling the Unknown: Genetic and Environmental Factors Behind Cleft Lip and Palate

17:30 07.09.2024 (Updated: 12:21 10.09.2024) Christina Glazkova

Writer / Editor

Longread

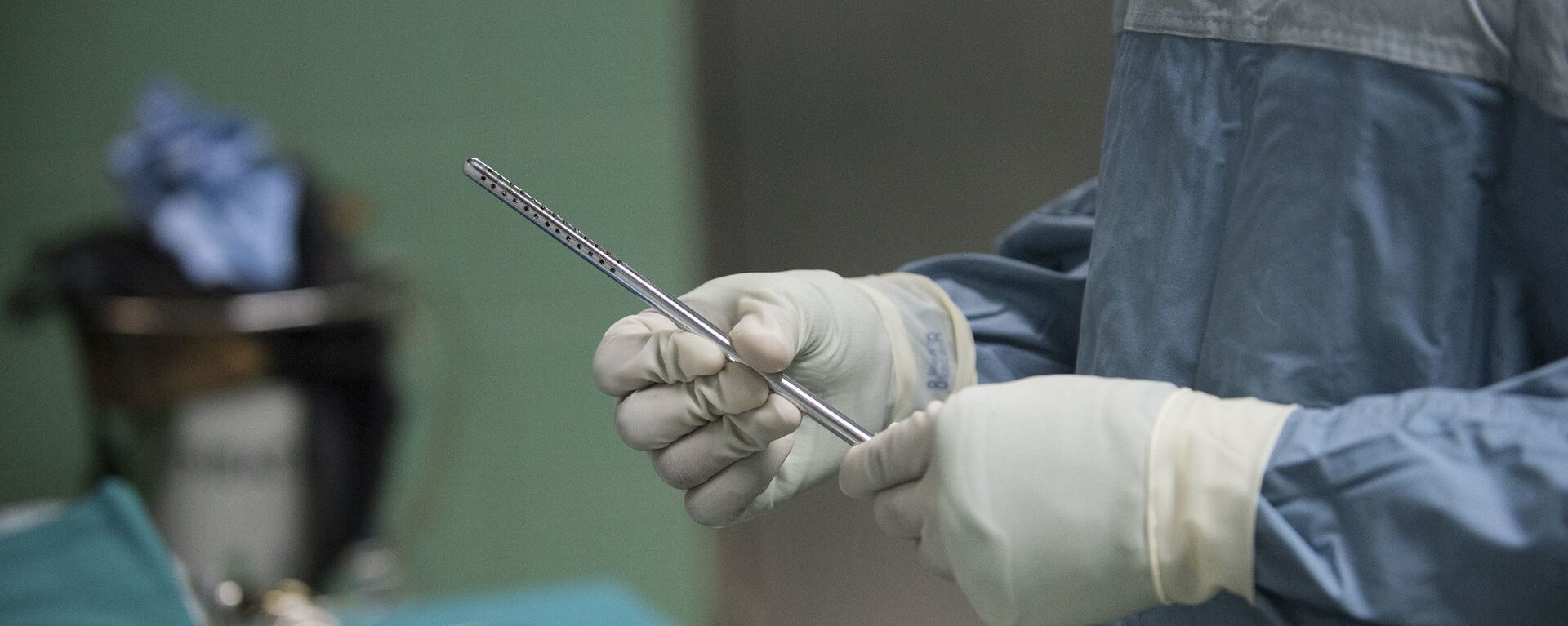

A cleft lip and palate are congenital conditions where a baby is born with openings or splits in the upper lip and the roof of the mouth (palate). A cleft lip affects the lip itself, causing a noticeable gap, while a cleft palate involves an opening in the roof of the mouth, which can affect eating, speaking, and hearing.

Only about 5% of cleft lip and palate cases can be traced back to genetics, leaving a staggering 95% in the realm of the unknown,

Professor Anil Madaree, Head of the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine, University of

Kwa-Zulu Natal, told

Sputnik Africa.

This uncertainty points to a complex interaction between genetic makeup and environmental factors that researchers have yet to fully unravel.

"There is a connection between the gene-environment association," said professor Madaree. "Certain environmental conditions will cause it, like malnutrition or maybe during the pregnancy, the mother's not getting enough vitamins, etc., but we're not exactly sure."

Cleft lip surgeries are typically performed when the

child is between 3 and 4 months old, while cleft palate surgeries usually occur between 9 and 12 months of age. Post-operative care is crucial, particularly for cleft palate cases, where diet and feeding must be carefully managed to prevent complications.

"The feeding is more important in the cleft palate," the professor explained, emphasizing the need for meticulous care to avoid the formation of fistulas, which create an unwanted communication between the mouth and nose.

Interestingly, in some parts of the world, such as

Southeast Asia, cleft conditions are more prevalent.

"It's mainly in Southeast Asia, places like Indonesia, Vietnam, and China. For some reason, the incidence there is probably the highest in the world," noted Madaree, contrasting this with the relatively lower incidence in Africa.

Yet, despite the lower prevalence, the challenges in Africa are significant due to the lack of awareness and medical infrastructure in many regions.

Addressing these challenges,

organizations like Operation Smile, with which Professor Madaree is deeply involved, work tirelessly to provide care and build local capacity. He emphasized that it's not only about performing surgeries, "but more importantly is to try and educate the local people, all the healthcare workers […] [to make] a long-lasting impact."

Looking to the future, Professor Madaree envisions the potential for

emerging technologies to revolutionize cleft treatment.

"It would be great if we could have an app [that] will tell you which the best type of surgery is to do [on a particular patient]. [...] And the other thing is that with artificial intelligence, you'll probably get robotic surgery to do [precise operations]," he said.

But even with existing technology, people with this condition get excellent results. Sputnik Africa talked to one of them to learn about his experience.

Tshepo Manetja's life changed when he was born with a cleft lip and palate. Although he received surgery to repair his cleft lip as a baby, the surgery for his cleft palate was repeatedly delayed. For years, Tshepo lived with the condition, until one day in 2018, he saw an advert for Operation Smile on DStv and reached out.

"I was nervous but so excited to finally be receiving surgery for a condition I’d had to live with all my life," Tshepo recalled.

In February 2019, Tshepo's long-awaited surgery was performed by Professor Madaree during Operation Smile's surgical program at Witbank Hospital in Mpumalanga. The surgery was successful, and for the first time, Tshepo experienced life without the gap in his

mouth.Now, with all his surgeries complete, Tshepo is on a new journey—getting his teeth straightened. Thanks to Operation Smile's continued support, he is receiving orthodontic treatment at Charlotte Maxeke Academic Hospital.

"I’m smiling from ear to ear and showing everyone my new shiny braces," Tshepo said with pride, determined not to miss a single checkup during his 18-month treatment.

As the medical community continues to explore the unknowns of cleft lip and palate, the hope is that with a blend of scientific discovery, technological advancement, and global collaboration, these conditions can be better understood and treated worldwide.